There is a scene in the movie Bridget Jones’s Diary where the single Bridget is attending a couples dinner party at the home of her only married girlfriend and is warned that she’d better hurry up and “get sprugged up” because the ubiquitous ‘clock is ticking’. Bridget is then asked the question that women like her – over 30 and unmarried bachelorettes across the world – dread to answer.

“Why is it there are so many unmarried women in their thirties these days, Bridget?” asks the smug husband of an acquaintance from across the table, with his pregnant wife at his side. Silence falls on the dining room as everyone sets down their utensils and all eyes converge on Bridget, almost expecting her to answer on behalf of every single woman in her thirties, everywhere.

Bridget belts a brief chuckle at the absurdity of the question, and says with a smile, “Oh, I don’t know. Suppose it doesn’t help that underneath our clothes our entire bodies are covered in scales.”

Sometimes I wish I could respond as she did at that moment when emotions of anxiety and embarrassment come together in piercingly sharp force in the centre of even many a resolute woman’s chest. Yet it is not always easy to take questions of postponed marriage in jest and good cheer. The stigma attached to being a single woman above 30 prevails in various cultures, which is why many of us can relate to Bridget, even if the cultural circumstances may differ tremendously.

Arab communities are particularly unforgiving of women who have not tied the knot by 30, and preferably many years younger. I was dismayed by the marriage question six years ago at 25 and I still wince when it is asked today at 31.

The obsession with marriage has made women view forming a family as the only culturally and religiously acceptable way to live their lives. Under this logic, no matter what she may have accomplished, a young Arab woman is doomed to be pitied and feel incomplete without a husband and kids. Some women are pressured to marry early and, as the years pass, to regard any man who has a job, is single and under 45–regardless of whether he happens to have a complementary personality– as a suitable match.

The preoccupation with marriage has caused many women to focus their happiness and fulfilment on securing another person’s affection, rather than realising peace within themselves beforehand. There is no use in crushing women’s self esteem as they get further into their 20s and enter their 30s simply because they have failed to cross paths with suitable men.

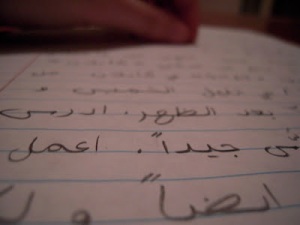

In an extreme example, the poster below, found in a Saudi elementary school, recently did its rounds on Twitter. It outlines a series of threats facing Muslim women, with an ominous image of a woman who appears to be gushing blood after being stabbed. Among warnings against listening to music and travelling abroad, proper Muslim girls are advised against “refusing or delaying marriage”. Rather than engendering a love of God in young girls they are taught to fear the wrath they would face if the pursuit of marriage is not their top priority.

By almost every measure outlined in the poster, I would be doomed – even though I hold family and marriage in very high regard. Family is the cornerstone of society. At a number of points in the Quran God advises us to be good to our parents, treat each other with respect and even informs us that He has created for us mates with whom we should deal with love and mercy. I hope to start a family and, if God wills, have children of my own.

But I struggle to find compelling religious justification for marrying young. Often, I would hear people say that children and wealth are ‘zinat hayat al-donya’ (adornments of this worldly life). This Arabic phrase excerpted from the Holy Quran has been regularly cited in my life as a justification for starting a family as early as possible; building a family unit is the primary purpose of a virtuous life.

As I grow deeper in my faith, the particular cultural emphasis on marriage and children puzzles me. When I read the Quran for the first time last year, I realised that the second part of that phrase was excluded from the popular discourse I had often been exposed to. “Wealth and children are (but) adornment of the worldly life. But the permanent righteous deeds are better in your Lord’s Sight (to attain) rewards, and better in respect of hope.” (Quran, 18:46)

God appears to be advising us to avoid becoming fixated on the pleasures we find in the money we earn and children we have. These things offer us a comfort in life but what endure for God are our righteous deeds, not our pursuit of family or wealth. God further calls on us repeatedly to be tolerant, to accept all of His blessings with gratitude and challenges with patience. So by extension, there is no contradiction in being single and being virtuous.

People’s faith in God-granted destiny (naseeb) often wavers when it comes to marriage. Our communities are prone to placing the onus of blame on the shoulders of the single women themselves rather than trying to address the real challenges facing our societies with meaningful solutions. From the perspective of myself and other single Muslim women, there are a limited number of options available for us to meet like-minded Muslim men. Introductions happen quite infrequently as family or friends take a more and more inactive role in our personal lives.

I am lucky to have very supportive family members, including my mother, who would not pressure me to wed. Nevertheless, there are moments of weakness where I am advised on how ‘a mediocre marriage is better than no marriage at all’. I have had my fair share of experiences with ill-fated love and awkward rendez-vous with men who had little compatibility with me other than that they happened to be single.

Single Arab women are often assumed to be too difficult, too picky, too ambitious or too head-strong to qualify as marriageable material. Quite to the contrary, most of the unmarried, over-30 women I know are considerate, intelligent, attractive, tolerant, family-oriented and chaste. Very little differentiates them from married women and most of us are not going around rejecting every guy who comes by. The point is that ‘the one’ – be he Mr. Right, Mr. Wrong, or Mr. Adequate– hasn’t yet come a knocking for whatever reason.

Last year, I was having lunch with an acquaintance, a young Arab woman some five years younger than myself, who told me she did not want to become that girl who is alone at 30 (she assumed I was about 27). She appeared almost terrified at the prospect. I consider myself to be successful, compassionate and more attractive now than I was at 25, and yet so many women fear the cultural marginalisation they would face if they turned out like me.

More and more, I regard such perceptions about the suitable age for marriage as a sign of cultural distortion and oversight of faith. Finding men who are willing to consider choosing a 32-year-old over a 23-year-old has, sadly, frequently turned into a search for the exception to the rule in Arab Islamic circles.

Yet when Prophet Muhammad ﷺ recounted his monogamous marriage to his first wife Khadija, 15 years his senior, he did so with unparalleled reverence. Their 25-year marriage was full of harmony, and he is known to have described Khadija as his intimate friend and his wise counsellor and companion. Responding to one of his later wife’s claims that God had blessed him with better, more youthful brides than Khadija after her death, the Prophet ﷺ has been cited as saying: “Indeed Allah did not grant me better than her; she accepted me when people rejected me, she believed in me when people doubted me; she shared her wealth with me when people deprived me; and Allah granted me children only through her”.

There are simple lessons in this: we must have faith in the spirit of God’s message, and be tolerant, patient and progressive in our expectations when dealing with issues of marriage. If a woman is destined to marry at 40 and have four children, as Khadija did, it will happen. If God wills her to marry at 23 and be barren, that too will come to pass. Just because most women fall somewhere between the two extremes does not diminish the importance of accepting that God tests each of us in different ways. Marriage is not a magic ticket to salvation.

The next time someone asks me why I am not married yet I hope I can come up with as witty a response as Bridget’s, something that will, with any luck, cause the person to pause for a moment and call into question their question.

——

Look forward to your comments!